If you were an aficionado of the female form in 1950s America, the name of Betty Page was probably at the top of your list. If you were an aficionado living in Britain, however, your list would be topped by another name – Pamela Green. While Betty Page virtually dropped from sight in 1957, after less than a decade of modeling, Pamela continued until the late 1970s, enjoying a career that spanned four decades.

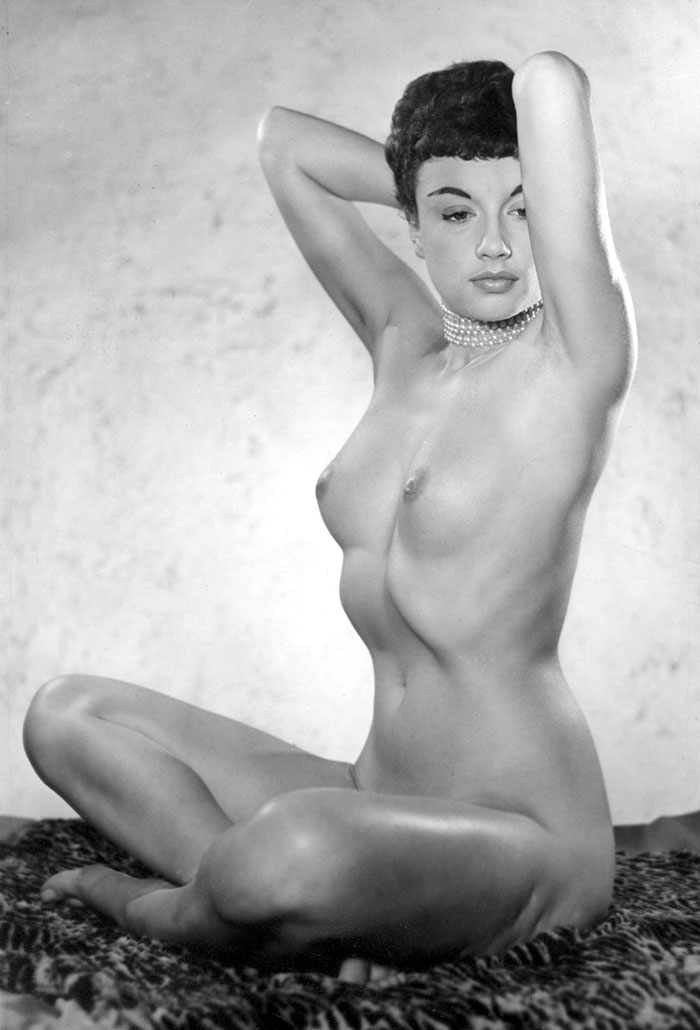

During this time, she was the subject of what I consider to be the most striking photographs of the female nude ever done. Far from being mere “girlie pictures”, these photos were elevated to a level formerly only occupied by oil paintings. Pamela worked with a number of prominent photographers and produced, like Bunny Yeager in America, a great deal of her own work. She combined the skills of a dancer, painter and model with her God-given beauty and created a vast body of work that stands as an unequaled monument to taste and talent.

What follows is a compilation of historical facts garnered from articles, taped interviews from British radio, and answers to my correspondence and phone calls. It is a fascinating chronicle of Pamela’s career, beginning in the late ’40s and continuing to the present day. As you will discover, Pamela is a witty, charming lady and a pleasure to get to know.

* * *

Posing for the Camera for the First Time

Pamela got her start doing nude modeling for photographers at the tender age of seventeen. This was due more to economics than anything else, since things were tight right after the Second World War. Prior to this, she had done some modeling and “life modeling” [nude modeling] for art classes in her school to defray the costs of her art education. She was paid four shillings and sixpence an hour for costume sittings, and five shillings for nude sittings.

“One day a friend of mine said, ‘You know, if you work for photographers they pay you a Guinea [21 shillings, or a pound and 1 shilling] an hour.’ So I thought, ‘Well, that’s a bit better’, so I went up Greek Street and I found a photographer called Douglas Webb and I banged on his door and I said, ‘Are you interested in figure models?’ and he said, ‘Well yes, let’s have a look first.’ So I undressed and he took some photographs. I did a sitting for him with a lot of white lilac, which I remember he’d nicked out of his mum’s garden (laughs). His mum was not best pleased.”

All went well until it came time to sign the release form for the session. Doug Webb noticed a particular article of clothing Pam was donning.

“He said, ‘What are you putting on?’ I said, ‘My school scarf.’ He said, ‘Good God! How old are you?’ I said, ‘Seventeen’.”

Doug informed Pamela of the need for parental permission for such work. This, surprisingly, turned out to be no problem, as Pamela’s folks trusted her better judgment.

“I don’t think she [her mother] minded in the slightest. My family were very open. I mean, there was no shame about nakedness. My father … was a very good artist, and used to love drawing nudes. He eventually did a wood sculpture of me in the nude and it was just one of those things. She trusted me. She said, ‘You wouldn’t do anything silly’, and in those days the photographers were very straight – they were very good – there were no problems ever.”

On the photographer’s side of it, Doug relates his memories of how it was back then:

“There was never a written law laid down on the age of a model to pose for photographs, only the age of consent, which at the time we are talking about was twenty-one. The legality of a model release signed by a minor who was under the age of twenty-one would be the only problem if the picture was published without the permission of the parents or legal guardian. It was possible to publish photographs of naked children, and indeed to take them without restriction, perfectly legally.

“To give you some idea, it is the custom of people of Greek and Indian origin to have their children photographed completely nude, whatever sex, to show everyone that the child is without any blemish, and complete with all limbs, fingers, and toes. How they get on now I don’t know because no photographer would be able to take these pictures. There was never a law that defined what was permissible. The police would initiate a prosecution and the case would be judged by a magistrate under the Vagrancy Act of 1604.”

Given the situation today, it seems amazing that such openness existed in the 1940s. What is also striking, in our litigious times, was the paucity of laws pertaining to the subject then. How things have changed!

That fortuitous first session led to much work for Pamela with Doug Webb, a number of camera clubs, other top photographers [such as Bertram Park, Angus McBean, John Craven, Zoltan Glass, Bill Brandt and Weegee], commercials and fashion house “corset work” [undergarment modeling].

Corset Work and the Folies-bergère

“The fashion models were a bit ‘iffy’ about this and didn’t want to do corset work. It wasn’t quite the thing, but if you did corset work, you got paid two Guineas an hour, so it was very profitable.”

That was during the day. At night, Pamela performed in a number of “Folies-Bergere” type reviews. At one casino, she worked as a nude, stand-in dancer. Stand-in dancers did just what the name implies, for a dancer at that time wasn’t allowed to actually dance in the nude.

“Nudes were not allowed to move on stage in ’47 or ’59.” Pam wrote in a letter, making her point emphatically. “Move, and they closed the show.”

Pamela was asked in a BBC interview about the opportunities open to her at the time.

“I might have gone on from there. I had the chance of going to Miami but it was a bit ‘iffy’ because it was evident that they put this girl in a golden cage and everybody chucked their keys in, and whoever got the key, got the girl! So I decided that wasn’t for me. And the other one was the Nouvelle Eve in Paris, or the Folies-Bergere, but I was determined really to go on with modeling.”

The more I learned about Pamela, the more impressed I became with her dedication to her art. She regards her body as an artisan regards his or her tools – something to be cared for in order to do professional work. The reason is evident when you read the comments of Doug Webb.

“I suppose I was one of the few people in London, or anywhere in England who could say, ‘Yes, well go in there. Take your clothes off. I’ll have a look at you,’ but that’s how we used to work because it’s difficult to describe what girls could do to their figure. But some of them, seventeen and eighteen, have done unbelievable things and of course, the thing is, if you’re going to do really good pictures you’ve got to have a good body to photograph and you’ve also got to have one that’s got no scars or marks on it. Of course, a lot of girls have had operations – appendix, peritonitis – all sorts of things, and surgeons are not too worried about what they leave behind as far as [scars], or certainly weren’t in those days. I think the cosmetic thing goes a bit deeper now, but in those days they really used to leave horrendous scars, and of course that was the main concern, because my stuff was sold all over the world and in America in particular, they were very, very particular about those sort of things.”

At seventeen, Pamela had a striking figure, as her early photographic work attests to, and she took the requirements of her craft seriously. Her body was her instrument and she cared for it like the artist she indeed was. In addition to the usual dietary restrictions, there were many other considerations to take into account. The type of photography Pamela did – artistic nudes – demanded it of her. It was her chosen path and she chose to walk it well. She took great pains to prepare herself for what made her name a byword in Great Britain and Europe.

All of the things Pamela studied were put to use. Her artist’s training was one of the colors on her pallet, as were her dance lessons. Because of this, she was considered a pleasure to work with. In a letter, I asked Doug how Pamela was to photograph.

“Pamela has the rare gift of posing not just her body perfectly, but also hands and feet as well, all in one movement.” Doug wrote. “This is the result of her dance training and the ability to take direction and concentrate on what she is doing, to the extent of moving a quarter-of-an-inch one way or another. Also, [she gave] a very great feeling of wanting the very best result possible, even when she was a paid model. Very many girls were a drag to work with, with the feeling that this was a job to be done through to earn money. Also, many of them do not know their right from their left.”

Practicing Nudist

While listening to a taped BBC interview, I heard Pamela mention that she was a practicing nudist. I asked her in a letter if nude modeling led her to nudism. The answer I received was further testament to her dedication to her work.

“I joined a nudist camp in order to obtain an even tan,” Pamela wrote in response. “No photographer would use a model with suntan marks.”

Life as a Model

To the person viewing nude photos, a life of scampering naked in front of the camera might seem like fun and games. According to Pamela, however, it is often hard and demanding work. As an example of this, Pamela related to me the following humorous anecdote in one of her letters. Again, it serves to underline her commitment to her art.

“I wore no restricting underwear or clothing when I was due to model, so there were no pressure marks on my body. On this occasion, I only wore a black cloak, fastened at the neck by a clasp. At the end of the day’s shooting, I was cold, tired and hungry. We had a forty-mile drive back to where we were staying with friends. Doug stopped in Bodmin, a small town in the middle of the Cornish moors and went to buy us some fish and chips from a local shop. As I got out of the car and was standing in the middle of the main street, the clasp of my cloak broke and my cloak fell to my feet, leaving me facing holiday makers and oncoming traffic – stark naked! I was too cold to care; I just bent down and picked the cloak up.”

Often, embarrassment was the least of Pamela’s problems during a shoot. At times, her sessions took on the air of an ordeal.

“When we [Pamela and Doug] were working in Cornwall, one November off Watergate Bay, [it] was bitterly cold. What I used to do, I would pour olive oil all over my body. That kept the cold out, and if you wanted the effect of water, I would whip into the sea, come out in a hurry, and all the water drops would be on me. I could do that for about twenty minutes before, as he [Doug] said, ‘You’re no good to me, you’re turning blue’, but I got used to it.”

In spite of the difficulties, Pamela was ever the trooper. Not only did she suffer for her art; she managed to do it with aplomb. This brush with the public, while Pamela and Doug were setting up for a shoot, shows how unflappable she could be.

“I had a marvelous thing that happened with the public. [It] was when we were working Watergate [Bay]. We were right down [on] the end. We got there, I undressed, left him [Doug] with the gear, walked ’round this rock-stack, and there was this seven-year-old boy holding a very tiny seagull chick and I had nothing on, except a scarf and long hair. ‘Oh Miss!’ he said, ‘He’s fallen out of his nest.’ and I thought ‘He doesn’t even realize I’m standing here with nothing on.’ So I said, ‘I’m not quite sure I know what you want.’ [He said,] ‘Well, couldn’t you climb the rock and put him back?’ Then his mum, who was a lifeguard, appeared with a brown and white spaniel and she wasn’t willing to climb the rock and Doug came ’round and said, ‘What’s going on?’ and the boy handed me this chick and it dived straight between the ‘bristols’! It was the warmest place to be, according to it. So there I was, with this seagull, and Doug said, “Look, put it down. We’ve got some work to do. We’ll think about it afterwards,’ and they went off and the boy still saying, ‘Oh, the poor seagull chick! It will drown!’

“At the end of the day I got dressed in a bikini, walked back, and there was the seagull chick sitting there and it ran towards me. I picked it up and it tucked itself inside the bikini top, wrapped my scarf [around it] and that was it! I was going to go home like that. So, in the end I said to Doug, ‘Try and climb.’ So he climbed the rock-stack and I handed him the [seagull chick] and he put it back and it did survive, ’cause I saw it the next day.”

Art Nudes Versus Pornography

I think it appropriate at this time to make an observation regarding “art nude” photography in general. To most, the distinction between “art nude” and pornographic, pictures is barely discernable. The fact that men are the primary buyers of such photos further muddies the waters, but there is a difference. Too often, the term “girlie”, or “nudie” pictures lumps the bad in with the good. Professionally done art nudes and many amateur examples as well, are of good quality, with well-posed models, often showing only their bosoms and discreetly displayed pubic areas. Old French postcard sets (the non-pornographic ones), for instance, were prime examples. Often denigrated as strictly naughty fare for perverts, they displayed a high degree of skill and artistic talent.

The primary differences between pornographic and art nudes is evident when you consider the subject matter. Pornographic photos show the most intimate aspects of the genitalia. Sometimes the very sex act itself is photographed. The “art nude” is a celebration of the entire human form, be it male or female. The genitalia are displayed but not emphasized. If a man and a woman are in the same photo, the sex act is never shown, or even simulated. The beauty of the human form, and the play of light on that form, is the subject. Women often smile at these explanations, especially when offered by enthusiastic males, but it is nevertheless a fact. The pornographic caters to lust; the “art nude”, while sensual and sometimes erotic, displays beauty.

Another factor to consider is the model’s face and eyes. If you look at art nudes, most of the time the model is not looking directly at the lens. She is on display like the subject of a still life. Only occasionally does she favor the viewer with a direct look, as if to say, “Yes, I’m a real woman.” The purpose here is not merely to titillate and excite male viewers but to create an appreciation for the artistic display of the female body. Pamela, in answer to a question concerning modesty vs. nudity, seems to second my thinking.

“It is a matter of taste. The female and male body has been used by artists since recorded time. Think of the Venus de Milo, ancient Egypt and even further back: Chinese art. While I was still an art student, I had hitchhiked around France and Italy in 1949 for the prime purpose of visiting the major art galleries. In Paris, I saw the nude paintings of Degas and Renoir, also the Venus de Milo in the Louvre. In Florence, I spent hours in front of the Botticelli painting The Birth of Venus and you can’t get more naked than that. I believe that a beautifully photographed nude is a work of art and in no way immodest; but there is a very fine line between modesty and prudishness. In that case there would be antagonism.”

In regard to prudishness, Pamela once participated in a 1964 BBC Woman’s Hour interview. She responded to an accusatory letter regarding a television show featuring her short film The Window Dresser in which she appeared nude.

“I can’t understand why a woman should be embarrassed or degraded by looking at a nude body. I don’t understand what there is degrading about a nude body – we’ve all got one. I’ve been a model now for about ten years, and in that time I have never come across this attitude from women. I started off – before I was a model I was an art student – and we used to do an awful lot of life drawing, and that’s why I think I never really sort of thought about [it]. If I’m nude, I don’t think of myself as naked.”

Another letter defending Pamela was received and read on the air. In it, the woman wrote she neither felt ashamed nor degraded, and asked what the difference was between painted nudes, which are considered art, and photographed nudes, which are not.

“I do see that,” Pamela agreed. “Because photography is a fairly new thing when it comes to nudes, and art has been accepted since, well, before Michelangelo. I suppose eventually they’ll start saying that nudes in photography are called art and nudes in some [other form], whatever the new medium may be, are disgusting.

“To my mind, a complete nude is not sexy. A partially clothed nude can be sexy, if you see certain programs and glamour shows where dresses are designed to show just so much cleavage, and the girls walk, sort of wiggling their behinds, to me this could be sexy. It could be corrupting if you like, but a complete nude, there’s no sex appeal attached to it at all really.”

When I asked Pamela about what advice she would give a young woman looking to embark on a career similar to hers, she offered this surprising answer.

“My advice would be – don’t. Ninety-nine percent of the pictures published today verge on the pornographic, if not actually so, and this is the kind of work that you would be asked to do.”

I thought her answer to be somewhat unequivocal, so I brought up the subject during a subsequent phone call. I asked her if she really felt there were no opportunities to do quality, non-pornographic nude work.

“Maybe one day in the future but at the present moment all the stuff, quite frankly, is semi-pornographic and, quite frankly, they use a girl once – they may pay her well – [but] they use it to death and that’s it. There is no market for really good nudes. Occasionally you may see one in an advertisement, but, on the whole, the stuff is, quite frankly, rubbish.”

I then asked about photography for the genre magazines, such as Femme Fatales.

“They’re looking at pictures like mine, which were done in the fifties and sixties. See, people like the time when Bridget Bardot was around and then Marilyn Monroe, when you had the truly beautiful women and actresses and real glamour. The youngsters today are curious and they like the look of it and older people of course. It’s nostalgia.”

In a 1993 interview on BBC radio, Pamela made the following observation.

“I think three-quarters of it [nudity today] is rubbish. I think also that it has gone so far with the magazines that you see that I don’t know where it’s going to stop. It’s no longer an artistic thing. It is – anything goes anything shows – and what do you follow on from that, really? The pictures from about 1967 to 1978, the stuff I did with Doug of course were different again, because, whereas you always had to shave [the pubic area], by the time you got to the seventies you didn’t have that problem anymore. You could pose better, a lot freer, do a lot more things, but I would never do anything like you see in the magazines that are on the very top shelf of Smith’s [a British convenience and magazine shop], that you can’t reach (laughs). I don’t know where it’s going to go to from here.”

In an Omnibus interview conducted by David McGillivray, which ironically took place at a nudist camp, Pamela was asked about the question of censorship.

“I think it has got to be, because everything gets put on video. Kids nowadays know how to handle a video [camera]; they are in the home. You can get very, very blue stuff – perversions. You can get things which might scare children, or put ideas in people’s minds who are not quite ‘with it’, and I think that there should be censorship and I think that also applies to magazines now.”

Sadly, this situation is often too true. The fact that these responses are from a woman, who made a career out of posing nude, further indicates just how far it has progressed.

Adventures on the Big Screen

Because she was so involved in still photography, Pamela’s “filmography” is a slim one. This is certainly not due to any lack of talent on her part. In fact, I find it remarkable how polished she was, working alongside far more experienced actors and actresses. This can be attributed to her theatrical training, as well as to a lot of natural talent. Here again, she called upon much of her past training and experience.

Although she only appeared in two short scenes in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) it is this film for which she is primarily known among fans, even though it was her first experience in the movies. Thinking back, Pamela recalls:

“In the entire film the only glamour/nude scenes were mine. In fact, the still that was always used to advertise the film in the Radio Times and newspapers was the one of Carl Boehm ‘posing’ me; the caption always reads ‘Carl Boehm and Pamela Green’.”

The amount of fame Pamela derived from her appearance was a testament to her reputation as a still photographer’s model. One would be hard pressed to remember that the film also featured the talents of ballerina Moira Shearer, from the Sadlers Wells Ballet Company, who also appeared in Powell’s film The Red Shoes (1948).

Fortunately, Peeping Tom was snatched out of the obscurity it was relegated to. The credit goes to film director Martin Scorcese, who liked the film and thought it deserved better. The restoration of this landmark film has produced a resurgence of interest in Pamela’s work, some 36 years after its release.

Other roles in major motion pictures were offered to Pamela. She appeared, fully clothed this time, in Val Guest’s The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961), and in Freddie Francis’ The Legend of the Werewolf (1975), which was her swan song as an actress.

Pamela also worked with George Harrison Marks, a long relationship that began in 1953 and lasted nearly fifteen years. Marks was known for his “art” magazines and 16mm short films, featuring beautiful women in unclothed situations. She figured prominently in Naked, as Nature Intended (1961), known in America by the shortened title As Nature Intended. More of a travelogue than a “skin flick”, the charmingly innocent film is replete with lots of nude scampering on the beach, ball tossing, and polite conversations among members of a nudist camp.

The emphasis is definitely on nudity, not sexuality. It was so idyllic; I wanted to order some brochures to consider for my next vacation. The only jarring note for me was one scene where a nudist mother, surrounded by her equally nude children and friends, was feeding an infant with, of all things, a baby bottle! Perhaps this nudist mother had reservations about breast-feeding in public?

Pamela also had a small part in Marks’ The Naked World of Harrison Marks (1965). Mostly, though, she starred in a number of Marks’ shorts made between 1953 and 1961: Chimney Sweeps [which actually had a theatrical run], Art for Art’s Sake, Gypsy Fire, The Window Dresser, Witch’s Brew, and Xcitement. Pamela also cast the other models, coached them in their nude scenes, worked as the wardrobe and art department, retouched the prints and handled management chores. Considering all the hats she wore, I wonder – did she also run the projector at screenings as well?

Though her movie parts pretty much came to an end when she left Marks, Pamela never really retired from photographic work. All of her prior experience served her in good stead later on, when; with Doug Webb [whom she married in 1967], she produced some of her finest still work. Calling upon past training, she worked with her husband behind the lens as well. Interestingly enough, she was involved in several movies from the other side of the lens. Working alongside her husband, she was involved with Casino Royale (1967), The Virgin and the Gypsy (1970), Perfect Friday (1970), Persecution (1974), The Ghoul (1975), and The Legend of the Werewolf (1975).

“I didn’t retire as such, but by 1979 we were so busy with other things. Doug was a stills photographer in both the film and television industry, and I became his assistant and we worked together as a team. Sometimes I had to teach actresses to pose – on one occasion in the nude. Pinewood studios would sometimes ‘borrow’ me to help in the print department, spotting and finishing hundreds of prints if they were short-staffed. I had a name as a good print finisher. I was responsible for all the photographs that appeared in my magazine Kamera.

As you know, Freddie Francis, who had been a very good friend of ours for many years, asked me to appear in his film The Legend of the Werewolf, when I was working on the film with Doug. It was great fun to do, and especially to work with Peter Cushing in front of, as well as behind, the camera. This all continued until 1986 when we moved to the Isle of Wight.”

Unexpected Revival

My acquaintance with Pamela Green began when I saw a few of her pictures, accompanied by a short letter, in Psychotronic Video Magazine #17. The quality of those photos, and the obvious beauty of their subject, impressed me, even though they were printed on newsprint. I wrote for a catalog. When Pamela’s reply arrived, along with an extensive catalog, I ordered a number of pictures on the strength of her descriptions alone. Pamela also offered her pictures in a five-picture set of postcard size. I found out later that this was a popular format. Pamela explains:

“This was something a lot of photographers did in London in the [’40s and] ’50s. It was a bit of some spare cash. They used to have five pictures, five postcards in a little cellophane bag, and they’d be in bookshops around Soho and Charing Cross Road. We met various people up at the Scala Cinema [at the launch of David McGillivray’s book Doing Rude Things (1992)] and they said, ‘Well, it’s nostalgia. Why don’t you do it again?’ and I thought, ‘Well I’ve got all the photos. I’ve got four thousand negatives.’ So I have made up a complete set. There’re about thirty-two sets and there’re 10 x 8 prints. The color that I had – Doug’s color – is very, very good and the color that I had from the late ’50s, which was beginning to go magenta, my labs up in Newmarket [in Suffolk, on the East coast, in horse-racing country] have restored fully. So I have a range of really lovely stuff that I’m selling.”

I was immensely pleased with photos I received from England in a couple of weeks. I ordered two sets of postcards and had Pamela pick out her favorite in each set to enlarge to 8 x 10. She also very graciously autographed them for me. In fact, one of the sets was with a model she worked with, Jean Sporle, and she even went to the trouble to get Jean to autograph them as well. I’ve ordered several more since then and struck up a correspondence that continues to this day.

Pamela recently completed a long-term project chronicling her long career in front of the camera. It is a 135-minute videotape, entitled Never Knowingly Overdressed, in which Pamela takes the viewer on a tour of her life as an art student, dancer, model and actress. The video includes five of the 8mm strip films she made with Harrison Marks, as well as a beautiful collection of over 500 of Pamela’s photographs, some set to music. I have the videotape and I can attest to the fact that it is truly a must for any collector of glamour photographs.

I find Pamela to be a delightfully friendly and helpful person. Recently, I “rang her up” and spent an enjoyable twenty minutes in conversation with her on the telephone. Pamela, interestingly enough, sounded exactly as I imagined she would, and displayed a warmth and sense of humor that put me totally at ease.

During that conversation, as I had written in a previous letter, I told her of my discussions with Kevin Clement about having her come to America to one of his Chiller Theatre conventions. She expressed her agreement with my idea, with the understanding that she would need sufficient time to prepare enough photographs for what I’m sure will be a long line of admiring convention attendees. Perhaps someday soon, I will have the honor of meeting her in person. It would be a grand day indeed for those of us in America, for we would have the opportunity to make the acquaintance of one of the all-time modeling legends – Pamela Green.

The Passing of Douglas Webb

On November 8, 1996, Pamela’s husband, Doug Webb, passed away at the age of 74. Pamela had a small funeral for him, attended by some of his WW II soldier friends, as Doug was one of the original “Dam Busters.” As a photographer, Doug’s work was legendary. He was of a time when one’s approach to work was to strive for the highest standards possible. This was reflected in the photography he did with Pamela, as well as his studio work and the stills he did for the movie industry. Doug, and his professional dedication to his art, will surely be missed.